There’s Nothing Wrong with Sentimentality in Art

by milk and honey beauty

Lobster-friends, a lot of art critics deride ‘sentimental’ art. Philosopher/critic Anthony Savile states that sentimental art is deceptive, promoting a “false picture of the world,” and an escape from reality.

No exhibit more poignantly captures the dichotomy between escapism and reality than “Pompeii, The Exhibition,” currently showing at the California Science Center in L.A. The gallery takes us on a tour of artifacts culled from Pompeii’s gorgeous villas and gardens – many of them heady with the scent of escapism and, yes, sentimentality. We know where all this is tending, of course. With horrible irony, the ‘post-volcano-eruption’ section of the gallery displays casts of Vesuvius’ victims, curled up, hands over mouths to shield them from the ash – they look horribly like sculptures; the kind that Pompeii’s many wealthy citizens commissioned for their gardens.

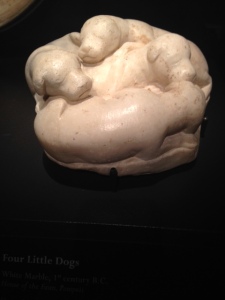

And yet…perusing this exhibit, none of the art from Pompeii feels like an escape from reality, though much of it is undeniably sentimental. Take a look at this adorable marble sculpture from a garden villa: as pristine as if it had been carved yesterday.

Evidently, this little quartet of dogs belonged to the villa’s owner, and desiring to capture them forever (goal achieved) the owner had them turned into art, only to be dug up years later during Pompeii’s excavation.

Maybe it’s me, but I see no ‘escape from reality’ here. There is nothing fantastic or escapist about emotion and love to my mind. Maybe when a work of art is overwrought with emotion to the point where it is melodramatic or unbelievable: yes, that’s another story. But to decry sentimental art in general seems like a gross misunderstanding of what sentimentality is. Far from being divorced from reality, sentiment allows us to connect in a visceral way with that which is, to us, most real. And for most of us that means our family, our children, our friends, cute kitty YouTube videos, our pets – essentially, our relationships. Not wars and bombs and poverty and death. Obviously, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t care about those things (of course we should) or that we should shy away from them. But to argue a point on the basis of what is and isn’t ‘real’ seems simultaneously sweeping and reductive.

“Four Little Dogs,” is not simply a charming, sentimental piece. It’s a powerful statement about what endures, and what has endured: the simple beauty of life, and of love.

I’ve looked long and again at the four little dogs and still am not sure I’d describe the piece as ‘sentimental’. Is it really trying to tell us what to feel? It looks to me quite a truthful record of animals being creaturely; not especially flattering to its subjects (the one in the foreground appears more porcine than canine, it’s so well fed) who appear blank with sleep rather than winsome.

Are certain topics, such as pets, inescapably sentimental?

LikeLike

Hmmm, good question! I feel that it’s sentimental, because it has the ‘ahhhhh!’ factor! Perhaps that’s not really a good test of sentimentality, but it’s maybe as good as any! And they are undeniably cute! But that’s what I mean, I guess- it is trying to invoke an ‘ahhh’ reaction (in my view) but that doesn’t make it any less ‘real.’

LikeLike